Combinatorics

BlueBox

Enumeration and Structure

Course Notes – MATH 501/2

![[Uncaptioned image]](x147.png)

LaTeX-ed on August 25, 2025

Alexander Hulpke

Department of Mathematics

Colorado State University

1874 Campus Delivery

Fort Collins, CO, 80523

{epigraphs}

\qitemTitle graphics:

Window in the Southern Transept of the Cathedral in Cologne (detail)

Gerhard Richter

These notes are accompanying my course MATH 501/2, Combinatorics,

held Fall 2025 at Colorado State University.

©2025 Alexander Hulpke. Copying for personal use is permitted.

1 Preface

Counting is innate to man.

History of India

Abū Rayhān Muhammad ibn Ahmad Al-Bīrūnī

This are lecture notes I prepared for a graduate Combinatorics course which ran in 2016/17, 2020/21, 2024 and 2025 at Colorado State University.

They started many years ago from an attempt to supplement the book [cameron] (which has great taste in selecting topics, but sometimes is exceedingly terse) with further explanations and topics, without aiming for the encyclopedic completeness of [stanley1, stanley2].

In compiling these notes, In addition to the books already mentioned, I have benefitted from: [cameron, cameronlint, godsilroyle, lidlniederreiterapp, lintwilson, hall, concrete, knuth3, reichmeider].

You are welcome to use these notes freely for your own courses or students – I’d be indebted to hear if you found them useful.

Fort Collins, \thedate

Alexander Hulpke

hulpke@colostate.edu

Chapter 0 Introduction

A

combinatorial structure is one which has combinatorial properties.

Combinatorial properties are those possessed by combinatorial structures. So

formal definitions are not getting us anywhere.

We shall leave combinatorial structure as an undefined term. […]Course on Undergraduate Combinatorics

Solomon Golomb and Andy Liu

1 What is Combinatorics?

If one looks at university mathematics classes around 1920, one already finds the basic pattern of many current courses. Single-variable analysis had already taken much of its present shape. Algebra had begun to formalize groups, rings, and fields — concepts that, a few years later, looked very much like what is taught today. Much of the theory of differential equations was known, and numerical methods lacked only the availability of fast computers. But there was little combinatorics beyond the basic counting formulas used in statistics. Combinatorics began to grow suddenly in the 1950s and 1960s, in part motivated by the advent of computers, and arguably did not have a standard list of topics until the 1980s or 1990s. It differs from many other areas of mathematics in that it was not driven by a small number of deep (often unresolved) problems, but by the observation that problems from seemingly different areas actually follow similar patterns and can be studied with similar methods. Its scope, in the broadest sense, is the study of the different ways objects can be related to one another.

This investigation naturally splits into three parts: The question of existence (Can certain configurations exist?) Counting the number of possible configurations. (If we can count them it often implies we have a good overview over what can exist.) And finding extreme, often optimal, cases.

This course looks at combinatorics split into two main areas, roughly corresponding to semesters: the first is enumerative combinatorics, the study of counting the different ways configurations can be set up. The second is the study of properties of combinatorial structures that consists of many objects subject to certain prescribed conditions.

2 Prerequisites

This being a graduate class we shall assume knowledge of some topics that have been covered in undergraduate classes. In particular we shall use:

Sets, Functions, Relations

We assume the reader is comfortable with the concept of sets and standard constructs such as Cartesian products. We denote the set of all subsets of by , it is called the power set of .

A relation on a set is a subset of , functions can be considered as a particular class of relations. We thus might consider a function as a subset of .

Another important class of relations are equivalence relations. Via equivalence classes they correspond to partitions of the set.

Induction

The technique of proof by induction is intimately related to the concept of recursion. It is assumed, that the reader is comfortable with the various variants (different starting values, referring to multiple previous values, postulating a smallest counterexample) of finite induction. We also might sometimes just state that a proof follows by induction, if base case or inductive step are obvious or standard.

1 Abstract Algebra

Abstract algebra is often useful in providing a formal framework for describing objects. We assume the reader is familiar with the standard concepts from an undergraduate abstract algebra class – groups, permutations (we multiply permutations from left to right), cycle form, polynomial rings, finite fields, and linear algebra.

2 Graph Terminology

This being a graduate class, the assumption is that the reader has encountered the basic definitions of graph theory – such as: vertex, edge, degree, directed/undirected, path, tree – already in an undergraduate class.

3 Calculus

It often comes as a surprise to students , that combinatorics – this epitome of discrete mathematics – uses techniques from calculus. Some of it is the classical use of approximations to estimate growth, but we shall also need it as a toolset for manipulating power series. Still, there is no need for the reader to worry that we would encounter messy approximations, convergence tests, or bathtubs that are filled while simultaneously draining.

3 OEIS

A problem that arises often in combinatorics is that we can easily describe small examples, but that it is initially hard to see the underlying patterns. For example, we might be able to count the total number of objects of small size, but will be unable to count how many there are of larger size. In investigating such situations, the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS, at oeis.org) is an invaluable tool that allows to look up number sequences that fit the particular pattern Given by a few values , and for many of these gives a huge number of connections and references . Sequences in this encyclopedia have a “storage number” starting with the letter ”A”, and we will refer to these at times by an indicator box OEIS A002106.

Chapter 1 Basic Counting

One of the basic tasks of combinatorics is to determine the cardinality of (finite) classes of objects. Beyond basic applicability of such a number – for example to estimate probabilities – the actual process of counting may be of interest, as it gives further insight into the problem:

-

•

If we cannot count a class of objects, we cannot claim that we know it.

-

•

The process of enumeration might – for example by giving a bijection between classes of different sets – uncover a relation between different classes of objects.

-

•

The process of counting might lend itself to become constructive, that is allow an actual construction of (or iteration through) all objects in the class.

The class of objects might have a clear mathematical description – e.g., all subsets of the set . In other situations the description itself needs to be translated into proper mathematical language. For example:

Definition 1 (Derangements, informal definition).

Given letters and addressed envelopes, a derangement is an assignment of letters to envelopes such that no letter is in the correct envelope.

(How many derangement of exist? This particular problem will be solved in section 5.)

Here the translation to more formal objects is that we consider the letters and envelopes to be numbered from to , and the assignment being a function. That is:

Definition 2 (Derangements).

For an integer , a derangement is a bijection on (i.e. a permutation), such that for all .

We will start in this chapter by considering the enumeration of some basic constructs – sets and sequences. More interesting problems, such as the derangements here, arise later if further conditions restrict to sub-classes, or if obvious descriptions could have multiple sequences describe the same object.

1 Basic Counting of Sequences and Sets

I am the sea of permutation.

I live beyond interpretation.

I scramble all the names and the combinations.

I penetrate the walls of explanation.

Lay My Love

Brian Eno

The number of elements of a set , denoted by (or sometimes as ) and called its cardinality, is defined111We only deal with the finite case here, there are generalizations for infinite sets as the unique , such that there is a bijective function from to .

There are three basic principles that underlie counting:

- Disjoint Union

-

If with , then .

- Cartesian product

-

.

- Equivalence classes

-

If we can represent each element of in different ways by elements of , then .

A sequence (or tuple) of length is simply an element of the -fold cartesian product. Entries are chosen independently, that is if the first entry has choices and the second entry , there are possible choices for a length two sequence. Thus, if we consider sequences of length , entries chosen from a set of cardinality , there are such sequences.

This allows for duplication of entries, but in some cases – arranging objects in sequence – this is not desired. In this case we can still choose entries in the first position, but in the second position need to avoid the entry already chosen in the first position, giving options. (The number of options is always the same, the actual set of options of course depends on the choice in the first position.) The number of sequences of length thus is , called222Warning: The notation has different meaning in other areas of mathematics! “ lower factorial ”.

This could be continued up to a sequence of length (after which all element choices have been exhausted). Such a sequence is called a permutation of . There are such permutations.

Next we consider sets of elements. While every duplicate-free sequence describes a set, sequences that have the same elements arranged in different order describe the same set. Every set of elements from thus will be described by different duplicate-free sequences. To enumerate sets, we therefore need to divide by this factor, and get for the number of -element sets from the count given by the binomial coefficient

Note (using a convention of ) we get that . It also can be convenient to define for or .

Often one counting process can be modified to count somewhat different objects: Consider compositions of a number into parts, that is ways of writing as a sum of exactly positive integers with ordering being relevant. For example are the 3 possible compositions of into parts.

To get a formula of the number of possibilities, write the maximum composition

which has plus-signs. We obtain the possible compositions into parts by grouping summands together to only have summands. That is, we designate plus signs from the given possible ones as giving us the separation. The number of possibilities thus is .

If we also want to allow summands of when writing as a sum of terms, we can simply assume that we temporarily add to each summand. This guarantees that each summand is positive, but adds to the sum. We thus count the number of ways to express as a sum of summands which is by the previous formula .

Check this for and .

Again, slightly rephrasing the problem, this is also the number of multisets, that is set-like collections in which we allow the same element to appear multiple times, with elements chosen from possibilities, the -th summand indicating how often the -th element is chosen.

Swapping the role of and , We denote by (the second equality follows from Prop.4 a) the number of -element multisets chosen from possibilities.

The results of the previous paragraphs are summarized in the following theorem:

Theorem 3.

The number of ways to select objects from a set of is given by the following table:

| Repetition | No Repetition | |

|---|---|---|

| Order significant | ||

| (sequences) | ||

| Order not significant | ||

| (sets) |

Note 1.1.

Instead of using the word significant some books talk about ordered or unordered sequences. I find this confusing, as the use of ordered is opposite that of the word sorted which has the same meaning in common language. We therefore use the language of significant.

2 Bijections and Double Counting

As long as there is no double counting, Section 3(a) adopts the principle of

the recent cases allowing recovery of both a complainants actual losses and

a misappropriator’s unjust benefit…

Draft of Uniform Trade Secrets Act

American Bar Association

In this section we consider two further important counting principles that can be used to build on the basic constructs.

Instead of counting a set of objects directly, it might be easiest to establish a bijection to another set , that is a function which is one-to-one (also called injective) and onto (also called surjective). Once such a function has been established we know that and if we know we thus have counted .

We used this idea already above when we were counting compositions by instead considering possible positions of plus signs.

As a further example, consider the following problem: We have an grid of points with horizontal and vertical connections (depicted in figure 1 for ) and want to count the number of different paths from the bottom left, to the top right corner, that only go right or up.

Each such path thus has exactly right steps, and up steps. We thus (this already could be considered as one bijection) could count instead sequences ( is right, is up) of length that contain exactly ones (and zeros). Denote the set of such sequences by .

To determine , we observe that each sequence is determined uniquely by the positions of the ones and there are exactly of them. Thus let be the set of all -element subsets of .

We define to assign to a sequence the positions of the ones, .

As every sequence has exactly ones, indeed goes from to . As the positions of the ones define the sequence, is injective. And as we clearly can construct a sequence which has ones in exactly given positions, is surjective as well. Thus is a bijection.

We know that , this is also the cardinality of .

Check this for , .

The second useful technique is to “double counting”, counting the same set in two different ways (which is a bijection from a set to itself). Both counts must give the same result, which can often give rise to interesting identities. The following lemma is an example of this paradigm:

Lemma 2.1 (Handshaking Lemma).

At a convention (where not everyone greets everyone else but no pair greets twice), the number of delegates who shake hands an odd number of times is even.

Proof 2.2.

we assume without loss of generality that the delegates are . Consider the set of handshakes

We know that if is in , so is . This means that is even, where is the total number of handshakes occurring.

On the other hand, let be the number of pairs with in the first position. We thus get . If a sum of numbers is even, there must be an even number of odd summands.

But is also the number of times that shakes hands, proving the result.

About binomial theorem I’m teeming with a lot o’ news,

With many cheerful facts about the square of the hypotenuse.

The Pirates of Penzance

W.S. Gilbert

The combinatorial interpretation of binomial coefficients and double counting allows us to easily prove some identities for binomial coefficients (which typically are proven by induction in undergraduate classes):

Proposition 4.

Let be nonnegative integers with . Then:

-

a)

.

-

b)

.

-

c)

(Pascal’s triangle).

-

d)

.

-

e)

.

-

f)

(Binomial Theorem).

Proof 2.3.

a) Instead of selecting a subset of elements we could select the

elements not in the set.

b) Suppose we want to count committees of people (out of ) with a

designated chair. We can do so by either choosing first the

committees and then for each team the possible chairs out of the committee

members. Or we choose first

the possible chairs and then the remaining committee members out of

the remaining persons.

c) Suppose that I am part of a group that contains persons

and we want to determine subsets of this group that contain people. These

either include me

(and further persons from the others), or do not

include me and thus from the other people.

d) We count the total number of subsets of a set with elements.

Each subset can be described by a sequence of length , indicating

whether the -th element is in the set.

e) Suppose we have men and women and we want to select groups of

persons. This is the right hand side.

The number of possibilities with

exactly women is by a).

The left hand of the equation simply sums these over all possible .

f) Clearly is a polynomial of degree . The coefficient for

gives the number of possibilities to choose the -summand when multiplying

out the product

of factors so that there are such summands overall. This is simply the number of -subsets, .

Prove the theorem using induction. Compare the effort. Which method gives you more insight?

3 Stirling’s Estimate

Since the factorial function is somewhat unhandy in estimates, it can be useful to have an approximation in terms of elementary functions. The most prominent of such estimates is given by Stirling’s formula. Our description follows [fellerstirling]:

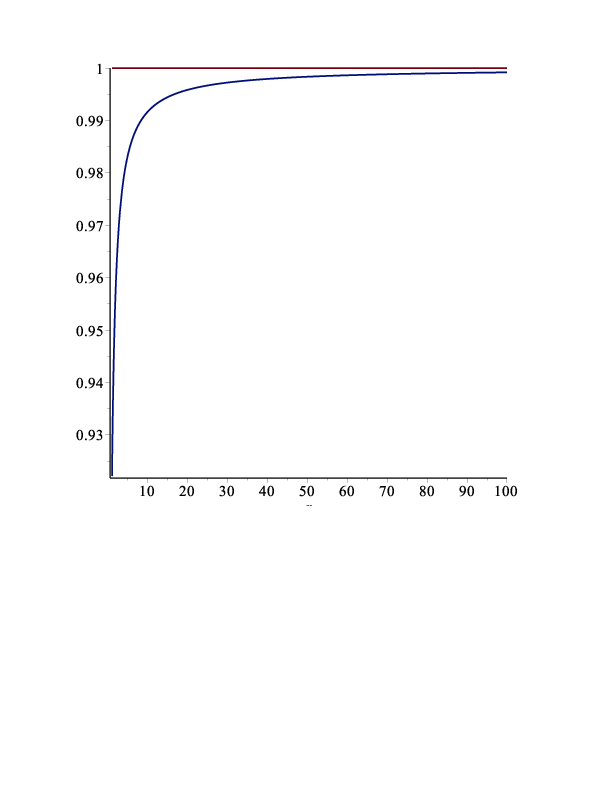

Theorem 5.

| (1) |

Here means that the quotient of the estimate and the true value is bounded by , that is the relative error is . Figure 2 shows a plot of the ratio of the estimate to .

Proof 3.1.

Consider the natural333all logarithms in this book are natural, unless stated differently logarithm of the factorial:

If we define a step function , we thus have that is an integral of . We also know that

We thus need to consider the integral over . To avoid divergence issues, we consider this in two parts. Let

and

Then

A substitution gives

from which we see that . By the Leibniz’ criterion thus converges to a value and we have that

Taking the exponential function we get that

with .

Using standard analysis techniques, one can now show that ; see [fellerstirling] for details. Alternatively, in concrete calculations, we could simply approximate the value to any accuracy desired.

The appearance of might seem surprising, but the following example shows that it arises naturally in this context:

Proposition 6.

The number of all sequences (of arbitrary length) without repetition that can be formed from objects is .

We note that no sequence can have length more than , as this would require repetition.

Proof 3.2.

If we have a sequence of length , there are sequences of length . Summing over all values of we get (with an index shift, replacing by ):

Using the Taylor series for we see that

This is an example (if we ignore language meaning) of the popular problem how many words could be formed from the letters of a given word, if no letters are duplicate.

If we allow duplicate letters the situation gets harder. For example, consider words (ignoring meaning) made from the letters of the word COLORADO. The letter O occurs thrice, the other five letters only once. If a word contains at most one O, the formula from above gives such words.

For more than one O, the above formula can’t be used any longer, but we need to go back to summations. If the word contains two O, and other letters there are options to select these letters and possibility to arrange the letters (the denominator 2 making up for the fact that both O cannot be distinguished). Thus we get

such words.

If the word contains three O, and other letters we get a similar formula, but with a cofactor , reflecting the arrangements of the three O which yield the same word. We thus have

possibilities, summing up to possibilities in total.

Lucky we do not live in MISSISSIPPI!

4 The Twelvefold Way

A generalization of counting sets and sequences is given by considering functions between finite sets. We shall consider functions with and . These functions could be arbitrary, injective, or surjective.

What does the concept of order (in)significant mean in this context? If the order is not significant, we actually only care about the set of values of a function, but not the values on particular elements. That is, all the elements of are equivalent, we call them indistinguishable or unlabeled (since labels will force objects to be different). Otherwise we talk about distinguishable or labeled objects.

Formally, we are counting equivalence classes of functions, in which two functions are called -equivalent, if there is a bijection such that for all .

Similarly, we define an -equivalence of function, calling s and equivalent, if there is such that for all . If we say the elements of are indistinguishable, we count functions up to -equivalence.

We can combine both equivalences to get even larger equivalence classes, which are the case of elements of both and being indistinguishable.

(The reader might feel this to be insufficiently stringent, or wonder about the case of different classes of equivalent objects. We will treat such situations in Section LABEL:polya under the framework of group actions.)

This setup ( and distinguishable or not and functions being injective, surjective or neither) gives in total possible classes of functions. This set of counting problems is called the Twelvefold Way in [stanley1, Section 1.9] (and attributed there to Gian-Carlo Rota).

For each of the 12 categories, give an example of a concrete counting problem in common language. Say, we have balls and boxes (either of them might be labeled), and we might require that no box has more than one ball, or that every box contains at least one ball.

Say, we have and . Then we have the following functions :

- All functions:

-

There are 9 functions, namely (giving functions as sequences of values):

- Injective functions:

-

There are 6 functions, namely

- Surjective functions:

-

There are no such functions, but there are 6 functions from to , namely:

- Up to permutation of

-

So we consider only the sets of values, which gives 6 possibilities:

- Injective, up to permutation of

-

The values need to be different, so 3 possibilities:

- Surjective, up to permutation of

-

There are no such functions, but there are 2 such functions from to , namely:

- Up to permutations of

-

Since , the question is just whether the two values are the same or not:

- Injective, up to permutations of

-

Here is the only such function.

- Surjective, up to permutations of

-

Again, no such function, but from to there are 3 such functions namely

- Up to permutations of and

-

Again two possibilities, but if , there are three possibilities, namely

- Injective, up to permutations of and

-

Again, is the only such function.

- Surjective, up to permutations of and

-

Again, no such function, but from to there is one, namely .

We are now getting ready to give formulas for the number of functions in each class, depending only on and . For this we introduce the following definitions. Determining closed formulae for these is not always easy, and will require further work in subsequent chapters.

A partition of a set is a collection of subsets (called parts or cells) such that for all :

-

•

-

•

for .

Note that a partition of a set gives an equivalence relation and that any equivalence relation on a set defines a partition into equivalence classes.

Definition 7.

We denote the number of partitions of into (non-empty) parts by . It is called the Stirling number of the second kind444There also is a Stirling number of the first kind OEIS A0082h7. The total number of partitions of is given by the Bell number OEIS A000110

There are partitions of the set .

Again we might want to set unless .

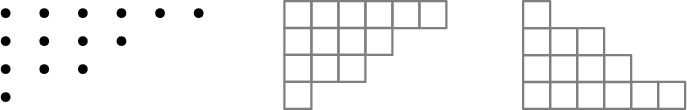

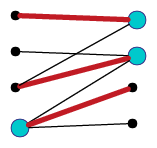

In some cases we shall care not which numbers are in which cells of a partition, but only the size of the cells. (That is, we only care about writing as a sum over an increasing sequence of positive integers: .) Sometimes this is called an integer partition, a Young diagram, or a Ferrers diagram555The difference between the last two is purely in whether we draw boxes or circles.. Figure 3 shows these diagrams for partition . In one style (called ”English”), the length of rows decrease as one goes downwards, in another (”French”) they do as one goes upwards.

We denote the number of partitions of into parts (ignoring which numbers are in which part) by , the total number of partitions by . OEIS A000041.

Again we study the function later, however here we shall not achieve a closed formula for the value.

We have , but . This is because the three partitions , , all have the same cell size pattern.

1 The twelvefold way theorem

We now extend the table of theorem 3:

Theorem 8.

if are finite sets with and , the number of (equivalence classes of) functions is given by the following table. (In the first two columns, d/i indicates whether elements are considered distinguishable or indistinguishable. The boxed numbers refer to the explanations in the proof.):

| arbitrary | injective | surjective | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | d | |||

| i | d | |||

| d | i | |||

| i | i |

Proof 4.1.

If is distinguishable, we can simply write the elements of in a row and consider a function on as a sequence of values. In 1), we thus have sequences of length with possible values, in 2) such sequences without repetition, both formulas we already know.

If such a sequence takes exactly values, each value can be taken to indicate the cell of a partition into parts, into which is placed. As we consider a partition as a set of parts, it does not distinguish the elements of , that shows that the value in 9) has to be . If we distinguish the elements of we need to account for the possible arrangements of cells, yielding the value in 3).

Similarly to 9), if we do not require to be surjective, the number of different values of gives us the number of parts. Up to different parts are possible, thus we need to add the values of the Stirling numbers.

To get 12) from 9) and 10) from 7) we notice that making the elements of indistinguishable simply means that we only care about the sizes of the parts, not which number is in which part. This means that the Stirling number gets replaced by the partition (shape) count .

If we again start at 1) but now consider the elements of as indistinguishable, we go from sequences to sets. If is injective we have ordinary sets, in the general case multisets, and have already established the results of 4) and 5).

For 6), we interpret the distinct values of to separate the elements of into parts. This is a composition of into parts, for which the count has been established.

In 8) and 11), finally, injectivity demands that we assign all elements of to different values which is only possible if . As we do not distinguish the elements of it does not matter what the actual values are, thus there is only one such function up to equivalence.

Chapter 2 Recurrence and Generating Functions

There’s al-gebra. That’s like sums with letters.

For…for people whose brains aren’t clever enough for numbers, see?

Jingo

Terry Pratchett

Finding a closed formula for a combinatorial counting function can be hard. It often is much easier to establish a recursion, based on a reduction of the problem. Such a reduction often is the principal tool when constructing all objects in the respective class.

An easy example of such a situation is given by the number of partitions of , given by the Bell numbers :

Lemma 0.1.

For we have:

Proof 0.2.

Consider a partition of . Being a partition, it must have in one cell. We group the partitions according to how many points are in the cell containing . If there are elements in this cell, there are options for the other points in this cell. And the rest of the partition is simply a partition of the remaining points.

1 Power Series – A touch of Calculus

A powerful technique for working with recurrence relations is that of generating functions. The definition is easy, for a counting function defined on the nonnegative integers we define the associated generating function as the power series

Here is the ring of formal power series in , that is the set of all formal sums with .

When writing down such objects, we ignore the question whether the series converges, i.e. whether can be interpreted as a function on a subset of the real numbers.

The reader interested in a rigorous, self-contained, presentation of the theory of formal power series, that does not require any reliance of results from analysis, can find it in [sambale2024].

Addition and multiplication are as one would expect: If and we define new power series and by:

With this arithmetic becomes a commutative ring. (There is no convergence issue, as the sum over is always finite.)

We also define two operators, called differentiation and integration on by

and

(with the integration constant is set as ).

Two power series are equal if and only if all coefficients are equal. An identity involving a power series as a variable is called a functional equation.

As a “shorthand”, pretending we knew nothing from Calculus (after all, we do not establish convergence), we define the following names for particular power series:

and note111All of this can either be proven directly for power series; alternatively, we choose in the interval of convergence, use results from Calculus, and obtain the result from the uniqueness of power series representations. that the usual functional identities , , and differential identities , hold.

A telescoping argument shows that for we have that , that is we can use the geometric series identity

to embed rational functions (whose denominators factor completely; this can be taken as given if we allow for complex coefficients) into the ring of power series.

For a real number , we define222Unless is an integer, this is a definition in the ring of formal power series. the generalized binomial coefficient as:

as well as a series representation of the -th power:

For obvious reasons we call this definition the binomial formula. Note that for integral this agrees with the usual definition of exponents and binomial coefficients, so there is no conflict with the traditional definition of exponents.

We also notice that for arbitrary we have that and .

Up to this point, generating functions seem to be a formality for formalities sake. They however come into their own with the following observations: Operations on the entries of a sequence, relations amongst its entries (such as recursion), or a sequence having been built on top of other sequences often have natural analogues with generating functions. Recursive identities amongst a coefficient sequence then become functional equations or differential equations for the generating functions.

If these equations have solutions, known start values typically give uniqueness of the solution, and (assuming it converges in an open interval), its power series representation must be identical to the generating function. Methods from Analysis, such as Taylor’s theorem, then can be used to determine expressions for the terms of the sequence.

Before describing this more formally, let us look at a toy example:

We define a function recursively by setting and . (This recursion comes from the number of subsets of a set of cardinality – fix one element and distinguish between subsets containing this element and those that don’t.) The associated generating function is . We now observe that

We solve this functional equation as

and (geometric series!) obtain the power series representation

this allows us to conclude that , solving the recursion (and giving the combinatorial result (which we knew already by another method) that a set of cardinality has subsets.)

1 Operations on Generating Functions

To prepare us for working with generating functions, let’s look in more detail on what generating function operations do with the coefficients.

For this, assume that and are sequences, associated to generating functions and , respectively.

We start with basic linearity. is the generating function associated to the sequence . The case is sometimes called the sum rule, describing the case that and count the cardinality of disjoint sets and the cardinality of their unions.

Shifting

Shifting the indices corresponds to multiplication by (positive or negative) powers of .

Differentiation

If , the derivative of corresponds to the sequence . This will allow for coefficients that also depend on the index position. This can often be used effectively together with shifts. For example, starting with the sequence , it corresponds (geometric series) to the generating function . Its derivative, thus corresponds to the sequence . Thus corresponds to the sequence . If we take a further derivative, we multiply each coefficient with its index position and shift back, resulting in a sequence of squares . The associated generating function will be the derivative function . We can shift once more to get the sequence , associated to the generating function .

Products

If we define a new sequence as sum of terms whose indices add up to a given value (this is sometimes called convolution):

its generating function will be . This is called the product rule.

One particular case of this is the summation rule: Suppose we define one sequence by summing over another: . We can interpret this as convolution with the constant sequence , whose generating function is . The generating function for the summatory sequence thus is .

Continuing the previous example, the sequence thus has the generating function .

The standard reference for generating functions is [generatingfunctionology]. The book [concrete] has a dedicated chapter, written on the level of an (advanced) undergraduate textbook.

We now make use of these tools by looking at general tools to find closed-form expressions for recursively defined sequences.

2 Linear recursion with constant coefficients

Then, at the age of forty, you sit,

theologians without Jehovah,

hairless and sick of altitude,

in weathered suits,

before an empty desk,

burned out, oh Fibonacci,

oh Kummer1, oh Gödel, oh Mandelbrot

in the purgatory of recursion.

1 also means: “grief”

Dann, mit vierzig, sitzt ihr,

o Theologen ohne Jehova,

haarlos und höhenkrank

in verwitterten Anzügen

vor dem leeren Schreibtisch,

ausgebrannt, o Fibonacci,

o Kummer, o Gödel, o Mandelbrot,

im Fegefeuer der Rekursion. Die Mathematiker

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

Suppose that satisfies a recursion of the form

That is, there is a fixed number of recursion terms and each term is just a scalar multiple of a prior value (we shall see below that easy cases of index dependence also can be treated this way). We also assume that initial values have been established. 333Some readers might have seen a linear algebra approach that solves such a recursion through the tool of matrix diagonalization. This approach results in the same characteristic polynomial and similar calculatory effort, but will not be generalizable in the same way as generating functions are.

The most prominent case of this are clearly the Fibonacci numbers OEIS A000045 with , recursion and initial values . We shall use these as an example.

Step 1: Get the functional equation

Using the recursion, expand the coefficient in the generating function with terms of lower index. Note that for the recursion does not hold, you will need to look at the initial values to see whether the given formula suffices, or if you need to add explicit multiples of powers of to get equality.

Separate summands into different sums, factor out powers of to get combined with .

Replace all expressions back with the generating function . The whole expression also must be equal to , this is the functional equation.

in the case of the Fibonacci numbers, the recursion is for . Thus we get, using the initial values , that

The functional equation is thus , respectively .

Step 2: Partial Fractions

We can solve the functional equation to express as a rational function in . (This is possible, because the functional equation will be a linear polynomial in .) Then, using partial fractions (Calculus 2), we can write this as a sum of terms of the form .

We solve the functional equation and obtain . For a partial fraction decomposition, let , , be the roots of the denominator polynomial . Then

We solve this as , .

Step 3: Use known power series to express each summand as a power series

The geometric series gives us that

If there are multiple roots, denominators could arise in powers. For this we notice that

and for an integer that

Using these formulae, we can write each summand of the partial fraction decomposition as an infinite series.

In the example we get

Step 4: Combine to one sum, and read off coefficients

We now take this (unique!) power series expression and read off the coefficients. The coefficient of will be , which gives us an explicit formula.

Continuing the calculation above, we get

and thus a closed formula for the Fibonacci numbers:

We notice that , thus asymptotically, as :

the value of the golden ratio.

1 Another example

We try another example. Take the (somewhat random, but involving an index-dependent term that makes it more complicated) recursion given by

We get for the generating function

(you should verify that the addition of was all that was required to resolve the initial value settings.)

We solve this functional equation as

and get (e.g. in Wolfram Alpha:

partial fractions (1+t+t^2)/(1-2*t)/(1+t)^2)

the partial fraction decomposition

an can read off the power series representation

solving the recursion as .

3 Nested Recursions: Domino Tilings

The Domino Theory had become

conventional wisdom and was

rarely challenged.

Diplomacy

Henry Kissinger

We now consider a number of problems that stem from counting arrangements of objects in the plane. While these counts themselves are not of deep importance, they produce nice examples of recursions.

Suppose we have tiles that have dimensions (in your favorite units) and we want to tile a corridor. Let be the number of possible tilings of a corridor that has dimensions . We can start on the left with a vertical domino (thus leaving to the right of it a tiling of a corridor of length ) or with two horizontal dominos (leaving to the right of it a corridor of length ). this gives us the recursion

with and (and thus to fit the recursion). This is again the Fibonacci numbers we have already worked out.

If we assume that the tiles are not symmetric, there are actually two ways to place a horizontal tile and itwo ways to place a vertical tile. We thus get a recursion with different coefficients,

with , (and thus ).

1 Multiple recursions

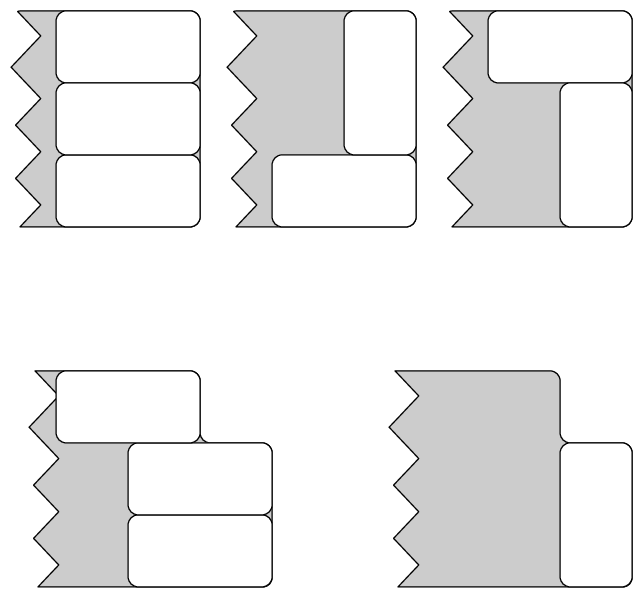

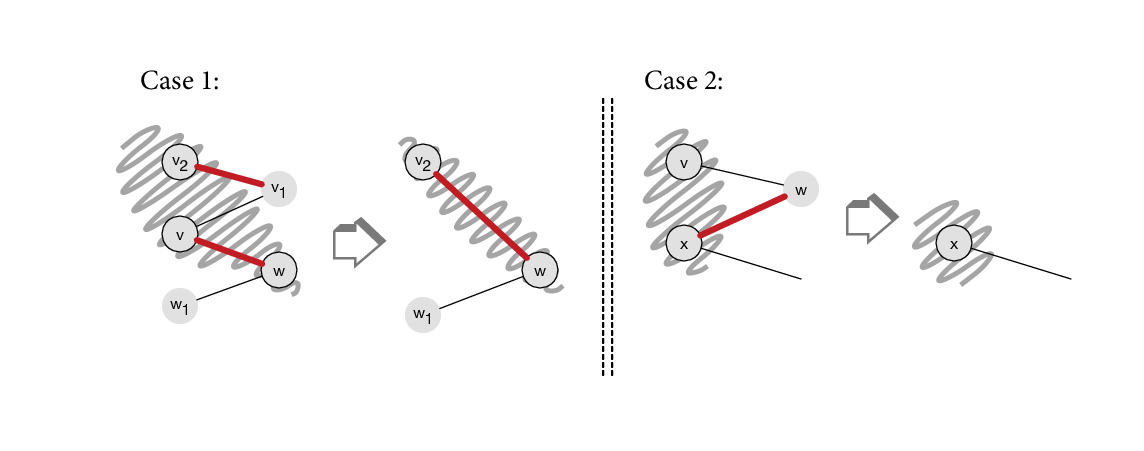

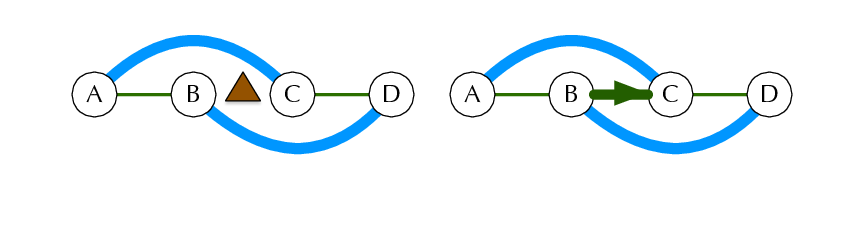

We go back to the assumption of symmetric tiles, but expand the corridor to dimensions . The recursion approach now seems to be problematic – it is possible to have patterns or arbitrary length that do not reduce to a shorter length, see figure 2.

We thus instead look only at the right end of the tiling and argue that every tiling has to end with one of the three patterns depicted in the top row of figure 3.

Removing these end pieces either produces a tiling of length , or a tiling of length in which the top (or bottom) right corner is missing. We thus introduce a count for tilings of length with the top right corner missing, the count for the bottom right corner missing will by symmetry be the same. The three possible end cases thus give us the recursion

Since we also need no know the values of , we build a recursive formula for them as well. Consider a tiling with the top right corner missing. It’s right end must be a vertical tile or two horizontal tiles. In this second case there also will have to be a further horizontal tile in the top row; the ends thus look as in the bottom row of figure 3.

This gives us the recursion

We use the initial values , , , , , and thus get the following identities for the associate generating functions

and

We solve this second equation as

and substitute into the first equation, obtaining the functional equation

which we solve for

This is a function in , indicating that for odd (indeed, this must be, as in this case is odd and cannot be tiled with tiles of area ). We thus can consider instead the function

with . Partial fraction decomposition, geometric series, and final collection of coefficients gives us the formula

and the sequence of given by OEIS A001835

If we consider wider corridors the recursions become more complicated. It is therefore somewhat surprising that it is possible to give a general formula for the number of ways of tiling an rectangle with dominoes. According to [temperleyfisher], it is

but its derivation is beyond the scope of this course.

4 Catalan Numbers

The induction I used was pretty tedious, but I do not doubt that this result could be obtained much easier. Concerning the progression of the numbers 1, 2, 5, 14, 42, 132, etc. …

Die Induction aber, so ich gebraucht, war ziemlich mühsam, doch zweifle ich nicht, dass diese Sach nicht sollte weit leichter entwickelt werden können. Ueber die Progression der Zahlen 1, 2, 5, 14, 42, 132, etc. … Letter to Goldbach

September 4, 1751

Leonard Euler

Next, we look at an example of a recursion which is not linear; we also use what is essentially the product rule:

Definition 9.

The -th Catalan number444Named in honor of Eugène Charles Catalan (1814-1894) who first stated the standard formula. The naming after Catalan only stems from a 1968 book, see http://www.math.ucla.edu/~pak/papers/cathist4.png. Catalan himself attributed them to Segner, though Euler’s work is even earlier. OEIS A000108 is defined555Careful, some books use a shifted index, starting at only! as the number of different ways a sum of variables can be evaluated by inserting parentheses.

We have , : and , and :

To get a recursion, consider the position of the “outermost” addition: suppose it is after of the variables have been encountered. On its left side is a parenthesized expression in variables, on the ride side is an expression in variables. We thus get the recursion

in which we sum over the products of lower terms.

This is basically the pattern of the product rule, just shifted by one.

We thus get the functional equation

(which is easiest seen by writing out the expression for and collecting terms). The factor is due to the way we index and 1 is due to initial values.

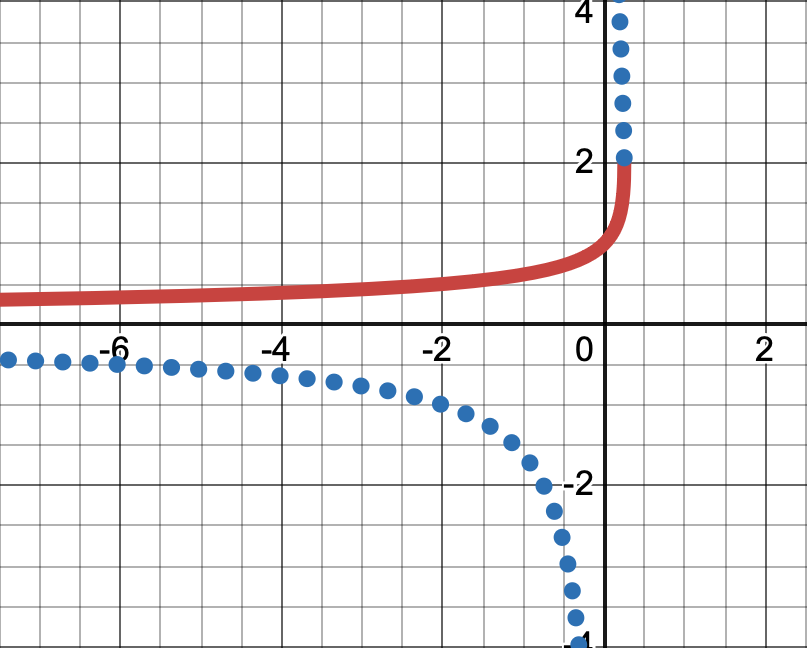

This is a quadratic equation in and yields the solution

The branch of the root was chosen so that the function has a limit, namely the value of , at . (The other branch yields a singularity, see Figure 4.)

The binomial series gives

We also observe that

Therefore

which shows that

Catalan numbers have many other combinatorial interpretations, and we shall encounter some in the exercises. Exercise 6.19 in [stanley2] (and its algebraic continuation 6.25, as well as an online supplement) contain hundreds of combinatorial interpretations.

5 Index-dependent coefficients and exponential generating functions

A recursion does not necessarily have constant coefficient, but might have a coefficient that is a polynomial in . In this situation we can use (formal) differentiation, which will convert a term into . The second derivative will give a term ; first and second derivative thus allow us to construct a coefficient and so on for higher order polynomials.

The functional equation for the generating function then becomes a differential equation, and we might hope that a solution for it can be found in the extensive literature on differential equations.

Alternatively, (using the special form of derivatives for a typical summand), such a situation often can be translated immediately to a generating function by using the power series

For an example of variable coefficients, we take the case of counting derangements OEIS A000166, that is permutations that leave no point fixed. We denote by the number of derangements on .

To build a recursion formula, suppose that is a derangement on . Then . We now distinguish two cases, depending on how is mapped by :

a) If , then swaps and and is a derangement of the remaining points, thus there are derangements that swap and . As there are choices for , there are derangements that swap with a smaller point.

b) Suppose there is such that . In this case we can “bend” into another permutation , by setting

We notice that is a derangement of the points .

Vice versa, if is a derangement on , and we choose a point , we can define on by

We again notice that is a derangement, and that different choices of and result in different ’s. Furthermore, the two constructions are mutually inverse, that is every derangement that is not in class a) is obtained by this construction.

There are possible derangements and choices for , so there are derangements in this second class.

We thus obtain a recursion

and hand-calculate666The reader might have an issue with the choice of , as it is unclear what a derangement on no points is. But we know that and , forcing this value for to make the recursion consistent. the initial values and .

From this recursion we could now construct a differential equation for the generating function of , but there is a problem: Because of the factor in the recursion, the values grow roughly like . The resulting series thus will have convergence radius , making it unlikely that a function satisfying this differential equation can be found in the literature.

We therefore introduce the exponential generating function which is defined simply by dividing the -th coefficient by a factor of , thus keeping coefficient growth bounded.

In our example, we get

and thus

We also have

From this, the recursion (written as ) gives:

and thus the separable differential equation

with .

Standard techniques from Calculus give the solution

of this differential equation. Looking up this function for Taylor coefficients (respectively determining the formula by induction) shows that

and thus (introducing a factor to make up for the denominator in the generating function) that

This is ,multiplied with a Taylor approximation of . Indeed, if we consider the difference to , the alternating series gives, for :

We have proven:

Lemma 5.1.

is the integer closest to .

That is asymptotically, if we put letters into envelopes, the probability is that no letter is in the correct envelope.

6 The product rule, revisited

Exponential generating functions have one more trick up their sleeve, arguably their most important contribution. For this, let us return to the product rule. It corresponds to the situation that the objects of a certain “weight”777The word “weight” indicates a size measurement, e.g. the number of vertices in a graph. can be described in terms of combining objects of lower weights (that sum up to the desired weight) in all possible ways.

This splitting-up however only considers the number of (sub)objects in each part, not which particular ones are in each part. In other words, we consider the constituent objects as indistinguishable.

Suppose now, however, that we are counting objects whose parts have identifying labels. In the example of the Catalan numbers this would be for example, if we cared not only about the parentheses placement, but also about the symbols we add, that is would be different from .

In such a situation, the recursion formula must, for each , account for which elements are chosen to be in the “left side”, with the rest being in the“right side”. Every combination is possible. That is, the recursion becomes:

We can write this as

which is the formula for multiplication of the exponential generating functions!

Let us look at this in a pathetic example, the number of functions from to (which we know already well as ).

Let count the number of constant functions on an -element set, that is . The associated exponential generating function thus is

(which, incidentally, shows why these are called “exponential” generating functions).

If we take an arbitrary function on , we can partition into (possibly empty) sets , such that is constant on and the are maximal with this property.

We get all possible functions by combining constant functions on the possible ’s for all possible partitions of . Note that the ordering of the partitions is significant – they indicate the actual values.

We are thus exactly in the situation described, and get as exponential generating function (start with , then use induction for larger ) the -fold product of the exponential generating functions for the number of constant functions:

The coefficient for in the power series for is , and hence the counting function is , as expected.

1 Bell Numbers

The integral -squared d,

From one to the cube root of three,

Times the cosine,

Of three pi over nine

Equals log of the cube root of e.

Anon.

We try this approach next to obtain an exponential generating function for the Bell numbers (though not a closed form expression for its coefficients):

Recall that the Bell numbers give the total number of partitions of and satisfy (Lemma 0.1) the recursion:

In light of the product rule, we insert a factor 1 and write this (after reindexing) as

and thus

If we denote the exponential generating function of the by , the right hand side thus will give the product of the generating function of the constant sequence (which we just saw is ) with . This reflects the split that gave us the recursion – into a set of size containing the number (the total number of such sets being once the numbers are chosen), and a partition of the remaining numbers.

The left hand side is the exponential generating function of which is just the derivative of , thus we have that

This is a separable differential equation, it’s solution is

for some constant . As we solve for and hence get the exponential generating function

There is no nice way to express the power series coefficients of this function in closed form, a Taylor approximation is (with denominators being deliberately kept in the form of to allow reading off the Bell numbers):

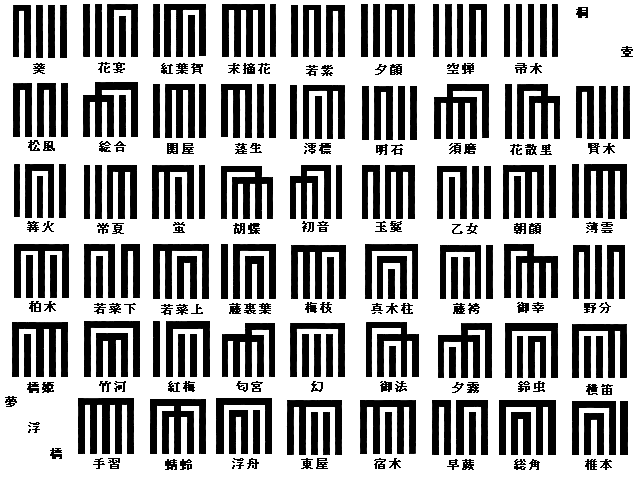

One, somewhat surprising, application of Bell numbers is to consider rhyme schemes. Given a sequence of lines, the lines which rhyme form the cells of a partition of . For example, the partition is the scheme AABBA used by Limericks, while Poe’s The Raven uses AABCCCBBB or

We can read off the Taylor expansion that . The classic 11th century Japanese novel Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji) has 54 chapters of which first and last are considered “extra”. The remaining 52 chapters are introduced each with a 5 line poem in one of the 52 possible rhyme schemes and a symbol illustrating the scheme. These symbols, see figure 5, the Genji-mon, have been used extensively in Art. See https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/topics_faq/genjimon.html

2 Stirling numbers

We apply the same idea to the Stirling numbers of the second kind, denoting the number of partitions of into (non-empty) parts. According to 8, part 3) there are order-significant partitions of into parts.

We denote the associated exponential generating function (for order-significant partitions) by

We also know that there is – apart from the empty set – exactly one partition into one cell. That is

If we have a partition into -parts, we can fix the first cell and then partition the rest further. Thus, for we have that

which immediately gives that

We deduce that the Stirling numbers of the second kind have the exponential generating function

Using the fact that , we thus get the exponential generating function for the Bell numbers as

in agreement with the above result.

We also can use the exponential generating function for the Stirling numbers to deduce a coefficient formula for them:

Lemma 6.1.

Proof 6.2.

We first note that – as – the -sum could start at or alternatively without changing the result.

Then multiplying through with , we know by the binomial formula that

and we read off the coefficients.

3 Involutions

Finally, let us use this in a new situation:

Definition 10.

A permutation on is called888Group theorists often exclude the identity, but it is convenient to allow it here. an involution OEIS A000085 if , i.e. for all .

We want to determine the number of involutions on points.

Consider the number of cycles (including -cycles, that is fixed points). Let be the number of involutions with exactly cycles. Clearly , , , , hence the exponential generating function for a single cycle is .

When considering an arbitrary involution, we can split off a cycle, seemingly leading to a formula

But (similar as when we considered a generating function for for the Stirling numbers), such a product of exponential generating functions will consider the arrangement of cycles, i.e. consider different from . We correct this by dividing by and thus get

and thus for the exponential generating function of the number of involutions a sum over all possible :

We easily write down a power series for the two factors

and multiply out, yielding

and thus (again introducing a factor of for making up for the exponential generating function)

Chapter 3 Inclusion, Incidence, and Inversion

It is calculus exam week and, as every time, a number of students were reported to require alternate accommodations:

-

•

students are sick.

-

•

students are scheduled to play for the university Quiddich team at the county tournament.

-

•

students are planning to go on the restaurant excursion for the food appreciation class.

-

•

students on the Quiddich team are sick (having been hit by balls).

-

•

students are scheduled for the excursion and the tournament.

-

•

students of the food appreciation class are sick (with food poisoning), and

-

•

of these students also planned to go to the tournament, i.e. have all three excuses.

The course coordinator wonders how many alternate exams need to be provided.

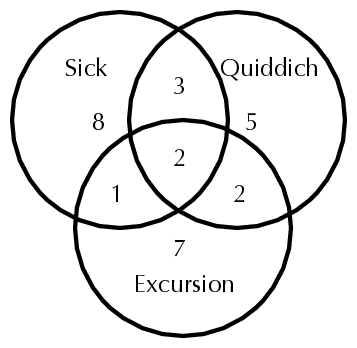

Using a Venn diagram and some trial-and-error, it is not hard to come up with the diagram in figure 1, showing that there are alternate exams to offer.

1 The Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion

By the method of exclusion,

I had arrived at this result,

for no other

hypothesis would meet the facts.

A Study in Scarlet

Arthur Conan Doyle

The Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion (PIE) formalizes this process for an arbitrary number of sets:

Let be a set and a family of subsets. For any subset we define

using that . Then

Lemma 1.1.

The number of elements that lie in none of the subsets is given by

Proof 1.2.

Take and consider the contribution of this element to the given sum. If for any , it only is counted for , that is contributes .

Otherwise let and let . We have that if and only if . Thus contributes

As a first application we determine the number of derangements on points in an different way:

Let be the set of all permutations of degree , and let be the set of all permutations with . Then is exactly the set of derangements, there are possibilities to intersect of the ’s, and the formula gives us:

For a second example, we calculate the number of surjective mappings from an -set to a -set (which we know already from 8 to be ):

Let be the set of all mappings from to , then . Let be the set of those mappings , such that is not in the image of , so . More generally, if we have that . The surjective mappings are exactly those in outside any of the , thus the formula gives us the count

using again that there are possible sets of cardinality .

The factor in a formula often is a good indication that inclusion/exclusion is to be used.

Lemma 1.3.

Proof 1.4.

To use PIE, the sets need to involve choosing from an , set, and after choosing of these we must choose from a set of size .

Consider a bucket filled with blue balls, labeled with , and red balls. How many selections of balls only involve red balls? Clearly the answer is the right hand side of the formula.

Let be the set of all -subsets of balls and those subsets that contain blue ball number , then PIE gives the left side of the formula.

We finish this section with an application from number theory. The Euler function counts the number of integers with .

Suppose that , and the integers in that are multiples of . Thus and for we have that consists of multiples of and thus . Then counts the number of elements in that do not lie in any of the and (inclusion/exclusion)

with the second identity obtained by multiplying out the product on the right hand side.

We also note – exercise LABEL:phisum – that . On its own this looks as if it is entirely separate from the inclusion/exclusion concept we just considered. But by generalize the concept of a hierarchy, given hitherto through inclusion of subsets, to more general situations, we shall see that this is a structural consequence of the previous formula.

2 Partially Ordered Sets and Lattices

The doors are open; and the surfeited grooms

Do mock their charge with snores:

I have drugg’d their possets,

That death and nature do contend about them

Macbeth, Act II, Scene II

William Shakespeare

A poset or partially ordered set is a set with a relation on the elements of which we will typically write as instead of , such that for all :

- (reflexive)

-

.

- (antisymmetric)

-

and imply that .

- (transitive)

-

and imply that .

The elements of a poset thus are the elements of , not those of the underlying relation and is cardinality is that of .

For example, could be the set of subsets of a particular set, and with be the “subset or equal” relation.

A convenient way do describe a poset for a finite set is by its Hasse-diagram. Say that covers if , and there is no with . The Hasse diagram of the poset is a graph in the plane which connects two vertices and only if covers , and in this case the edge from to goes upwards.

Because of transitivity, we have that if and only if one can go up along edges from to reach .

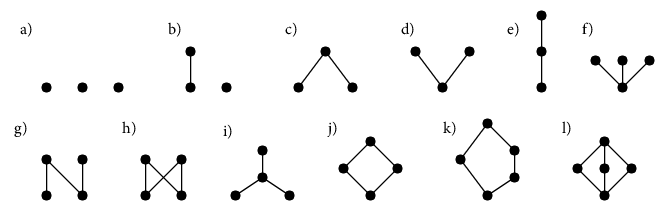

Figure 2 gives a number of examples of posets, given by their Hasse diagrams, including all posets on 3 elements.

An isomorphism of posets is a bijection that preserves the relation.

An element in a poset is called maximal if there is no larger (wrt. ) element, minimal is defined in the same way. Posets might have multiple maximal and minimal elements.

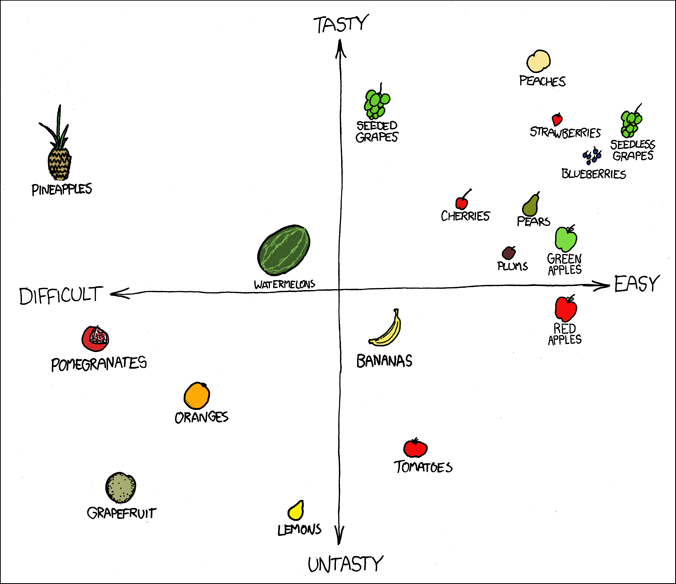

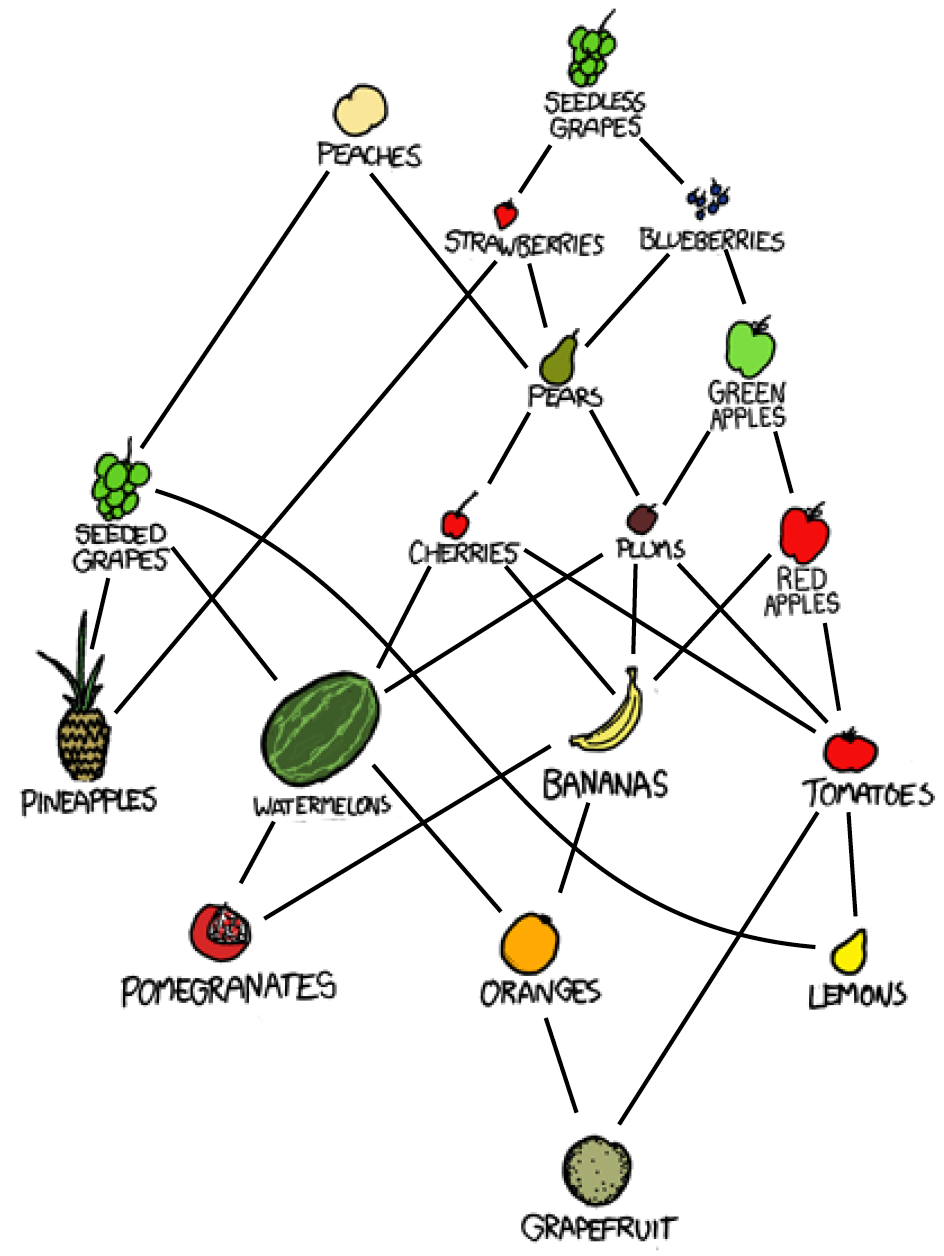

For another cute example 111Taken from lecture notes [axue] consider in Figure 3, left, the arrangement of fruits according to convenience and taste, as given by222pardon the title of the cartoon https://xkcd.com/388/.

R. Munroe, F*** Grapefruit, https://xkcd.com/388/, and [axue], p.108

We can read of a partial order from this by declaring a fruit as “better” than another, if it both more tasty and easier to consume. The resulting Hasse diagram is on the right side of Figure 3. It is easily seen that not every pair of fruits is comparable this way, and that there is no universal “best” or “worst” fruit.

1 Linear extension

My scheme of Order gave me the most trouble

Autobiography

Benjamin Franklin

A partial order is called a total order, if for every pair of elements we have that or .

While this is not part of our definition, we can always embed a partial order into a total order.

Proposition 11.

Let be a partial order on . Then there exists a total order (called a linear extension) such that .

To avoid set acrobatics we shall prove this only in the case of a finite set . Note that in Computer science the process of finding such an embedding is called a topological sorting.

Proof 2.1.

We proceed by induction over the number of pairs that are incomparable. In the base case we already have a total order.

Otherwise, let such an incomparable pair. We set (arbitrarily) that . Now let

We claim that is a partial order. As it has fewer incomparable pairs, this shows by induction that there exists a total order , proving the theorem.

Since is reflexive, is. For antisymmetry, suppose by contradiction that for some we have that . Since is a partial order, not both could have been in .

Thus assume (WLOG) that

This implies that and . If , this implies by transitivity that , contradicting the choice of . If , then also and thus by definition . Transitivity implies again in contradiction to the choice of .

For transitivity, the definition of implies that we cannot have transitivity for pairs in . Thus first suppose that and . Then , as otherwise . But then , implying that . The other remaining case is analog.

This theorem implies that we can always label the elements of a countable poset with positive integers, such that the poset ordering implies the integer ordering. Such an embedding is in general not unique, see Theorem 21.

The case of a totally ordered subset gets a special name:

Definition 12.

A chain in a poset is a subset of such that any two elements of it are comparable. (That is, restricted to the chain the order is total.)

2 Lattices

Definition 13.

Let be a poset and .

-

•

A greatest lower bound of and is an element which is maximal in the set of elements with this property.

-

•

A least upper bound of and is an element which is minimal in the set of elements with this property.

is a lattice if any pair have a unique greatest lower bound, called the meet and denoted by ; as well as unique least upper bound, called the join and denoted by .

Amongst the Hasse diagrams in figure 2, e,j,k,l) are lattices, while the others are not. Lattices always have unique maximal and minimal elements, sometimes denoted by (minimal) and (maximal).

Other examples of lattices are:

-

1.

Given a set , let the power set of with defined by inclusion. Meet is the intersection, join the union of subsets.

-

2.

Given an integer , let be the set of divisors of with given by “divides”. Meet and join are , respectively lcm.

-

3.

For an algebraic structure , let be the set of all substructures (e.g. group and subgroups) of and given by inclusion. Meet is the intersection, join the substructure spanned by the two constituents.

-

4.

For particular algebraic structures there might be classes of substructures that are closed under meet and join, e.g. normal subgroups. These then form a (sub)lattice.

Using meet and join as binary operations, we can axiomatize the structure of a lattice:

Proposition 14.

Let be a set with two binary operations and and two distinguished elements . Then is a lattice if and only if the following axioms are satisfies for all :

- Associativity:

-

and ;

- Commutativity:

-

and ;

- Idempotence:

-

and ;

- Inclusion:

-

;

- Maximality:

-

and .

Proof 2.2.

The verification that these axioms hold for a lattice is left as exercise to the reader.

Vice versa, assume that these axioms hold. We need to produce a poset structure and thus define that iff . Using commutativity and inclusion this implies the dual property that .

To show that is a partial order, idempotence shows reflexivity. If and then and thus antisymmetry. Finally suppose that and , that is and . Then

and thus . Associativity gives us that if also then

and thus , thus is the unique greatest lower bound. The least upper bound is proven in the same way and the last axiom shows that is the unique minimal and the unique maximal element.

Definition 15.

An element of a lattice is join-irreducible (JI) if and if implies that or .

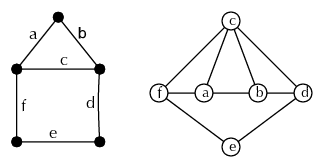

For example, figure 4 shows a lattice in which the black vertices are JI, the others not.

If we take the lattice of subsets of a set, the join-irreducibles are the 1-element sets. If we take divisors of , the join-irreducibles are prime powers.

When representing elements of a finite lattices, it is possible to do so by storing the JI elements once and representing every element based on the JI elements that are below. This is used for example in one of the algorithms for calculating the subgroups of a group.

3 Product of posets

The cartesian product provides a way to construct new posets (or lattices) from old ones: Suppose that are posets with orderings , , we define a partial order on by setting

Proposition 16.

This is a partial ordering, so is a poset. If furthermore both and are lattices, then so is .

The proof of this is exercise LABEL:posetproduct.

This allows us to describe two familiar lattices as constructed from smaller pieces (with a proof also delegated to the exercises):

Proposition 17.

a) Let and the power-set lattice (that is the subsets

of , sorted by inclusion). Then is (isomorphic to) the

direct product of copies of the two element lattice .

b) For an integer written as a product of

powers of distinct primes, let be the lattice of divisors of

. Then .

3 Distributive Lattices

A lattice is distributive, if for any one (and thus also the other) of the two following laws hold:

These laws clearly hold for the lattice of subsets of a set or the lattice of divisors of an integer .

Lattices of substructures of algebraic structures are typically not distributive, the easiest example (diagram l) in figure 2) is the lattice of subgroups of which also is the lattice of subspaces of .

If is a poset, a subset is an order ideal, if for any and we have that implies .

Lemma 3.1.

The set of order ideals is closed under union and intersection.

Proof 3.2.

Let be order ideals and and . Then or . In the first case we have that , in the second case that , and thus always . The same argument also works for intersections.

This implies:

Lemma 3.3.

The set of order ideals of , denoted by is a lattice under intersection and union.

As a sublattice of the lattice of subsets, is clearly distributive.

For example, if is the poset on 4 elements with a Hasse diagram given by the letter (figure 2, g) then figure 4 describes the lattice .

In fact, any finite distributive lattice can be obtained this way

Theorem 18 (Fundamental Theorem for Finite Distributive Lattices, Birkhoff).

Let be a finite distributive lattice. Then there is a unique (up to isomorphism) finite poset , such that .

To prove this theorem we use the following definition:

Definition 19.

For any element of the poset , let be the principal order ideal generated by .

Lemma 3.4.

An order ideal of a finite poset is join irreducible in if and only it is principal.

Proof 3.5.

First consider a principal order ideal and suppose that with and being order ideals. Then or , which by the order ideal property implies that or .

Vice versa, suppose that is a join irreducible order ideal and assume that is not principal. Then for any , is a proper subset of . But clearly .

Corollary 20.

Given a finite poset , the set of join-irreducibles of , considered as a subposet of , is isomorphic to .

Proof 3.6.

Consider the map that maps to . It maps bijective to the set of join-irreducibles, and clearly preserves inclusion.

We now can prove theorem 18

Proof 3.7.

Given a distributive lattice , let be the set of join-irreducible elements of and be the subposet of formed by them. By corollary 20, this is the only option for up to isomorphism, which will show uniqueness.

Let be defined by , that is it assigns to every element of the JI elements below it. (Note that indeed is an order ideal.). We want to show that is an isomorphism of lattices.

Step1: Clearly we have that for any (using the join over the empty set equal to ). Thus is injective.

Step 2: To show that is surjective, let be an order ideal of , and let . We aim to show that : Clearly every also has , so . Next take a join irreducible , that is . Then and thus

by the distributive law. Because is JI, we must have that for some , implying that . But as is an order ideal this implies that . Thus and thus equality, showing that is surjective.

Step 3: We finally need to show that maps the lattice operations: Let . Then if and only if and . Thus .

For the join, take . Then , implying , or (same argument) ; therefore . Vice versa, suppose that , so and thus

Because is JI that implies , respectively .

In the first case this gives and thus ; the second case similarly gives .

We close with a further use of the order ideal lattice:

Theorem 21.

Let be a poset of size . The number of different linear orderings of is equal to the number of different chains of (maximal) length in .

Proof 3.8.

Exercise.

4 Chains, Antichains, and Extremal Set Theory

Man is born free;

and everywhere he is in chains

The Social Contract

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

We start with a definition dual to that of a chain:

Definition 22.

An antichain in a poset is a subset, such that any two (different) elements are incomparable.

We shall consider partitions of (the elements of) a poset into a collection of chains (or of antichains).

Clearly a chain and antichain can intersect in at most one element. This gives the following duality:

Lemma 4.1.

Let be a poset.

a) If has a chain of size , then it cannot be partitioned in fewer

than antichains.

b) If has an antichain of size , then it cannot be partitioned in

fewer than chains.

A stronger version of this goes usually under the name of Dilworth’s theorem333proven earlier by Gallai and Milgram.

Theorem 23 (Dilworth, 1950).

The minimum number of chains in a partition of a finite poset is equal to the maximum number of elements in an antichain.

Proof 4.2.

The previous lemma shows that , so we only need to show that we can partition into chains. We use induction on , in the base case nothing needs to be shown.

Consider a chain in of maximal size. If every antichain in contains at most elements, we apply induction and partition into chains and are done.

Thus assume now that was an antichain in . Let

Then , as there otherwise would be an element we could add to the antichain and increase its size.

As is of maximal size, the largest element of cannot be in , and thus we can apply induction to . As there is an antichain of cardinality in , we partition into disjoint chains.

Similarly we partition into disjoint chains. But each is maximal element of exactly one chain in and minimal element of exactly one chain of . We can combine these chains at the ’s and thus partition into chains.

Corollary 24.

If is a poset with elements, it has a chain of size or an antichain of size .

Proof 4.3.

Suppose not, then every antichain has at most elements and by Dilworth’s theorem we can partition into chains of size each, so .

Corollary 25 (Erdős-Szekeres, 1935).

Every sequence of distinct integers contains an increasing subsequence of length at least , or a decreasing subsequence of at length least .

Proof 4.4.

Suppose the sequence is with . We construct a poset on elements by defining if and only if and . (Verify that it is a partial order!)

The theorems of this section in fact belong into a bigger context that has its own chapter, chapter 4, devoted to.

A similar argument applies in the following two famous theorems, that are part of foundational material of extremal set theory.

Theorem 26 (Sperner, 1928).

Let and , such that if . Then .

Proof 4.5.

Consider the poset of subsets of and let . Then is an antichain.

A maximal chain in this poset will consist of sets that iteratively add one new point, so there are maximal chains, and maximal chains that involve a particular -subset of .

We now count the pairs such that and is a maximal chain with . As a chain can contain at most one element of an antichain this is at most .

On the other hand, denoting by the number of sets with , we know there are

such pairs. As is maximal for we get

We note that equality is achieved if is the set of all -subsets of .

Theorem 27 (Erdős-Ko-Rado, 1961).

Let a collection of distinct -subsets of , where , such that any two subsets have nonempty intersection. Then .

Proof 4.6.

Consider “cyclic -sequences” with , taken “modulo ” (that is each number should be ).

Note that , since if some equals , then any only other must intersect , so we only need to consider (again considering indices modulo ) for . But will not intersect , allowing at most for a set of subsequent ’s to be in .

As this holds for an arbitrary , the result remains true after applying any arbitrary permutation to the numbers in . Thus

We now calculate the sum by fixing , and observe that there are permutations such that . Thus , proving the theorem.

5 Incidence Algebras and Möbius Functions

A common tool in mathematics is to consider instead of a set the set of functions defined on . To use this paradigm for (finite) posets, define an interval on a poset for a given pair as the set , and denote by the set of all intervals. (It might be convenient to set if .

For a field , we shall consider the set of functions on the intervals:

(with ) and call it the incidence algebra of . If we denote intervals by their end points , we shall write for if .

This set of functions is obviously a -vector space under pointwise operations. We also define a multiplication on by defining, for a function by

In exercise LABEL:incidencealgebra we will show that with this definition becomes an associative -algebra444An algebra is a structure that is both a vector space and a ring, such that vector space and ring operations interact as one would expect. The prototype is the set of matrices over a field. with a one, given by

We could consider as the set of formal -linear combinations of intervals and a product defined by

and extended bilinearily.

If is finite, we can, by theorem 11, arrange the elements of as where implies that . Then is, by exercise LABEL:incalgmatalg isomorphic to the algebra of upper triangular matrices where if .

Lemma 5.1.

Let . Then has a (two-sided) inverse if and only if for all .

Proof 5.2.

The property is equivalent to:

(implying the necessity of ) and

If the second formula will define the values uniquely, depending only on the interval . Reverting the roles of and shows the existence of a left inverse and standard algebra shows that both have to be equal.

The zeta function of is the characteristic function of the underlying relation, that is if and only if (and ).

This implies that

is the size of the interval.

By Lemma 5.1, is invertible. The inverse is called the Möbius function of the lattice . The identities

| (1) | |||||

| (2) |

follow from and allow for a recursive computation of values of and imply that is integer-valued.

For illustration, we shall compute the Möbius function for a number of common posets.

Lemma 5.3.

Let be the total order on the numbers . Then for any we have:

Proof 5.4.

The case of is trivial. If , the sum in 2 has only one summand, and the result follows. Thus assume that but . Then

and the result follows by induction on .

Lemma 5.5.

If , are posets, the Möbius function on satisfies

Proof 5.6.

It is sufficient to verify that the right hand side of the equation satisfies 2.

Corollary 28.

a) For , we have that

if , and 0 otherwise.

b) If are divisors of , then in we have that

if is the product of different primes, and 0

otherwise.

Part b) explains the name: is the value of the classical number theoretic Möbius function.

Part a) connects us back to section 1: The Möbius function gives the coefficients for inclusion/exclusion over an arbitrary poset. We will investigate and clarify this further in the rest of this section.

1 Möbius inversion

The property of being inverse of the incidence function can be used to invert summation formulas with the aid of the Möbius function: