What’s the probability that a random triangle is obtuse?

or:

What the heck is a random triangle, anyway?

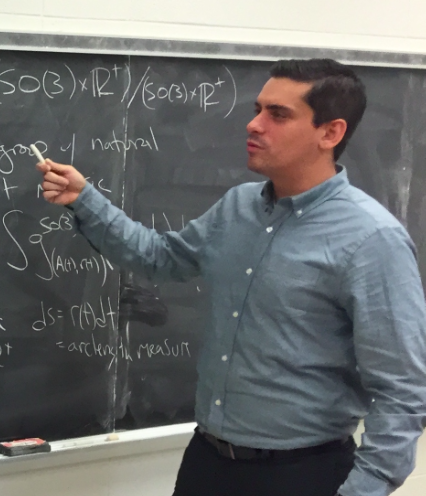

Collaborators

Jason Cantarella

U. of Georgia

Thomas Needham

Ohio State

Gavin Stewart

NYU

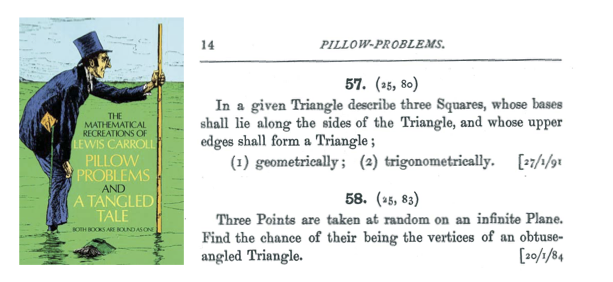

Lewis Carroll's Pillow Problem #58

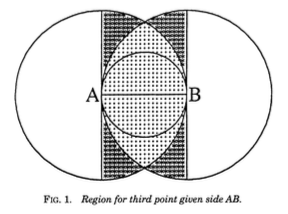

Carroll’s Answer

Suppose \(AB\) is the longest side. Then

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse})=\frac{\pi/8}{\pi/3-\sqrt{3}/4} \approx 0.64\)

But if \(AB\) is the second longest side,

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse}) = \frac{\pi/2}{\pi/3+\sqrt{3}/2} \approx 0.82\)

A Probabilist’s Answer

Proposition [Portnoy]: If the distribution of \((x_1,y_1,x_2,y_2,x_3,y_3)\in\mathbb{R}^6\) is spherically symmetric (for example, a standard Gaussian), then

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse}) = \frac{3}{4}\)

Consider the vertices \((x_1,y_1),(x_2,y_2),(x_3,y_3)\) as determining a single point in \(\mathbb{R}^6\).

For example, when the vertices of the triangle are chosen from independent, identically-distributed Gaussians on \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

Choose three vertices uniformly in the disk:

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse})=\frac{9}{8}-\frac{4}{\pi^2}\approx 0.7197\)

Restricted Domain?

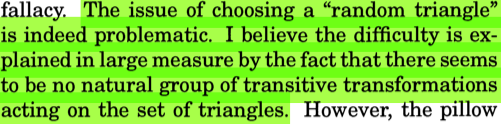

Choose three vertices uniformly in the square:

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse})=\frac{97}{150}-\frac{\pi}{40}\approx 0.7252\)

Random Triangles?

Is Carroll’s question really about choosing random points, or is it actually about choosing random triangles?

How would you choose a triangle “at random”?

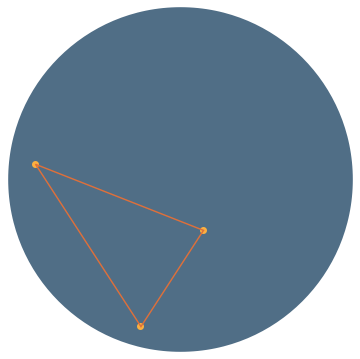

Angles?!

Remember from Geometry that three angles \((\theta_1,\theta_2,\theta_3)\) determine a triangle up to similarity (AAA).

\(\theta_1\)

\(\theta_2\)

\(\theta_3\)

What are the restrictions on the \(\theta_i\)?

\(\theta_1+\theta_2+\theta_3=\pi\)

\(0<\theta_1, 0 < \theta_2, 0<\theta_3\)

and

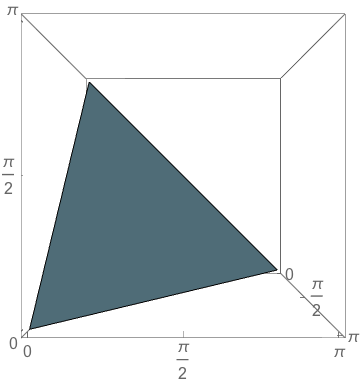

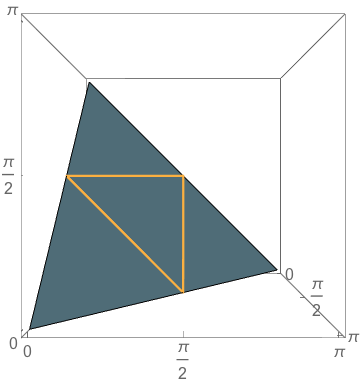

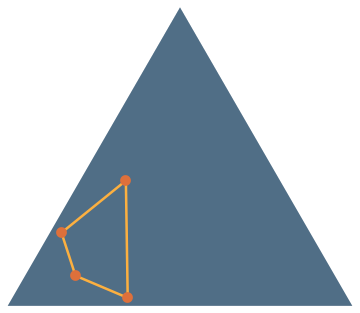

The Triangle of Triangles

\(\theta_1+\theta_2+\theta_3=\pi\)

\(0<\theta_1, 0 < \theta_2, 0<\theta_3\)

and

\(\theta_1=\pi/2\)

\(\theta_2=\pi/2\)

\(\theta_3=\pi/2\)

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse})=\frac{3}{4}\)

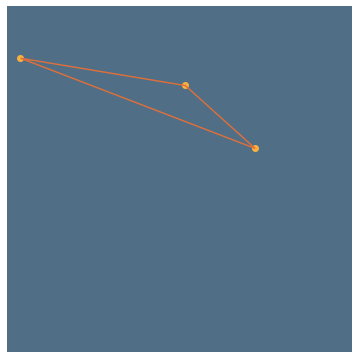

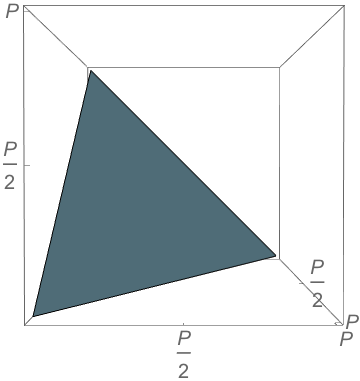

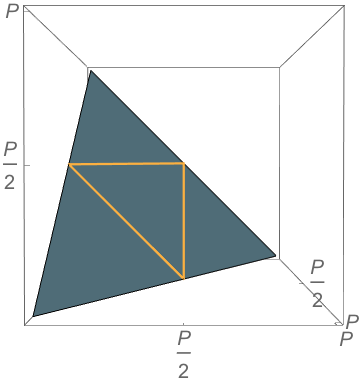

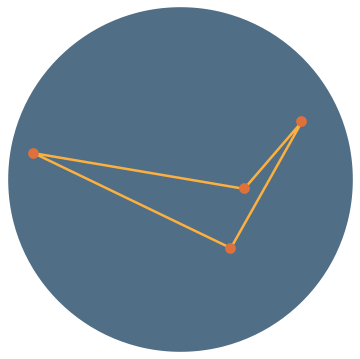

Side Lengths?!

Remember the sidelengths \((a,b,c)\) uniquely determine a triangle (SSS).

Obtuseness is scale-invariant, so pick a perimeter \(P\) and we have \(a+b+c=P\).

Problem

Not all points in the simplex correspond to triangles

\(b+c<a\)

\(a+b<c\)

\(a+c<b\)

Yet Another Pillow Problem Answer

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse})=9-12\ln 2 \approx 0.68\)

\(b^2+c^2=a^2\)

\(a^2+b^2=c^2\)

\(a^2+c^2=b^2\)

— Stephen Portnoy, Statistical Science 9 (1994), 279–284

Random Triangles...?

Translation for Geometers

The space of all triangles should be a (preferably compact) manifold \(T\) with a transitive isometry group. We should use the left-invariant metric on \(T\), scaled so vol\((T)=1\). Then the Riemannian volume form induced by this metric is a natural probability measure on \(T\), and we should compute the volume of the subset of obtuse triangles.

Ideally, this should generalize to \(n\)-gons.

Spoiler: \(T\simeq\mathbb{RP}^2=G_2\mathbb{R}^3\)

Back to Triangles

Let \(s=\frac{1}{2}(a+b+c)\) and define

Note: It’s convenient to choose \(s=1\).

\(s_a=s-a, \quad s_b = s-b, \quad s_c = s-c\)

Then

\(s_a+s_b+s_c=3s-(a+b+c)=3s-2s=s\)

and the triangle inequalities become

\(s_a>0, \quad s_b > 0, \quad s_c > 0\)

But there’s still no transitive group action!

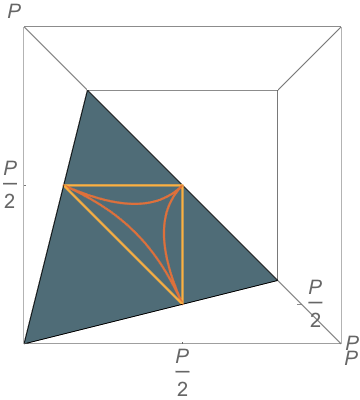

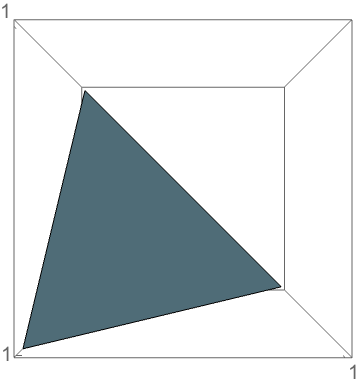

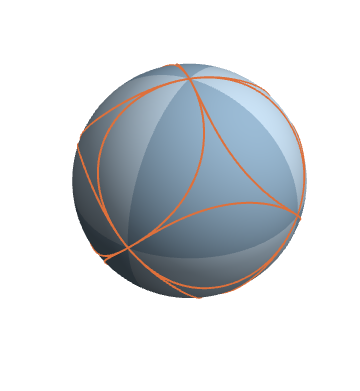

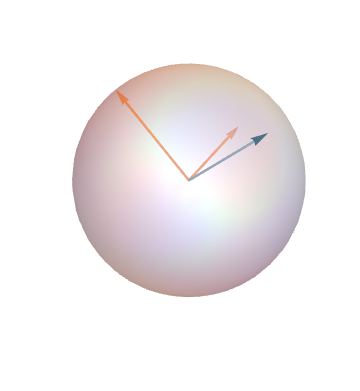

Take Square Roots!

Consider \((x,y,z)\) so that

\(x^2=s_a, \quad y^2 = s_b, \quad z^2 = s_c\)

The unit sphere is a \(2^3\)-fold cover of triangle space

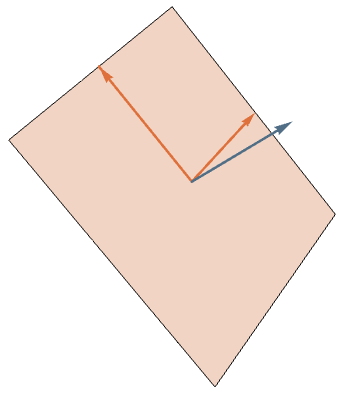

The Transitive Group

The rotations are natural transformations of the sphere, and the corresponding action on triangles is natural.

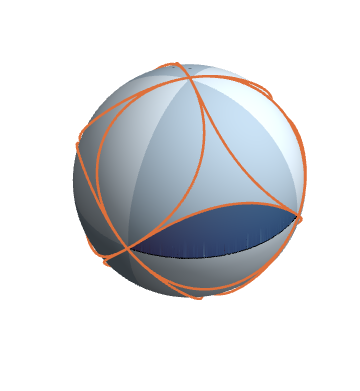

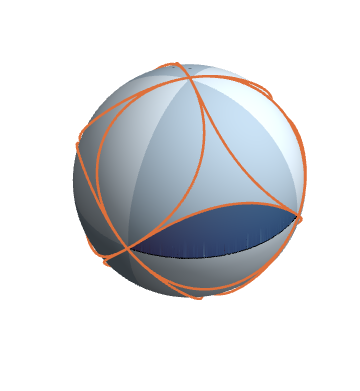

\(c=1-z^2\) fixed

\(z\) fixed

\(C(\theta) = (\frac{z^2+1}{2}\cos 2\theta, -z \sin 2\theta)\)

The equal-area-in-equal-time parametrization of the ellipse

A More Complicated Rotation

A Measure on Triangle Space

Since the uniform measure is the unique (up to scale) measure on \(S^2\) invariant under the action of \(SO(3)\)...

Definition

The symmetric measure on triangle space is the probability measure proportional to the uniform measure on the sphere.

Right Triangles

The right triangles are exactly those satisfying

\(a^2+b^2=c^2\) & permutations

Since \(a=1-s_a=1-x^2\), etc., the right triangles are determined by the quartic

\((1-x^2)^2+(1-y^2)^2=(1-z^2)^2\) & permutations

\(x^2 + x^2y^2 + y^2 = 1\), etc.

Obtuse Triangles

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse})=\frac{1}{4\pi}\text{Area} = \frac{24}{4\pi} \int_R d\theta dz\)

But now \(C\) has the parametrization

And the integral reduces to

Solution to the Pillow Problem

By Stokes’ Theorem

\(\frac{6}{\pi} \int_R d\theta dz=\frac{6}{\pi}\int_{\partial R}z d\theta = \frac{6}{\pi}\left(\int_{z=0} zd\theta + \int_C zd\theta \right)\)

\(\left(\sqrt{\frac{1-y^2}{1+y^2}},y,y\sqrt{\frac{1-y^2}{1+y^2}}\right)\)

\(\frac{6}{\pi} \int_0^1 \left(\frac{2y}{1+y^4}-\frac{y}{1+y^2}\right)dy\)

Our Answer

Theorem [w/ Cantarella, Needham, Stewart]

With respect to the symmetric measure on triangles, the probability that a random triangle is obtuse is

\(\frac{3}{2}-\frac{3\ln 2}{\pi}\approx0.838\)

Generalization

For \(n>3\), the sidelengths do not uniquely determine an \(n\)-gon, so the simplex approach doesn‘t obviously generalize.

Key Observation: The coordinates \((x,y,z)\) of a point on the sphere are the Plücker coordinates of the perpendicular 2-plane.

\(\vec{p}=\vec{a} \times \vec{b}\)

Planes and Polygons

In general, we can identify the collection of planar \(n\)-gons with \(G_2(\mathbb{R}^n)\), the Grassmannian of 2-planes through the origin in \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

Definition [w/ Cantarella & Deguchi]

The symmetric measure on \(n\)-gons of perimeter 2 up to translation and rotation is the pushforward of Haar measure on \(G_2(\mathbb{R}^n)\).

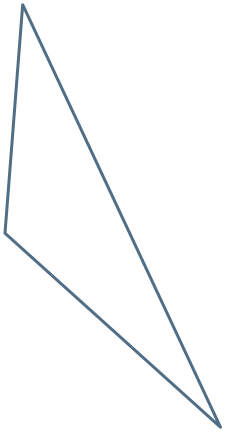

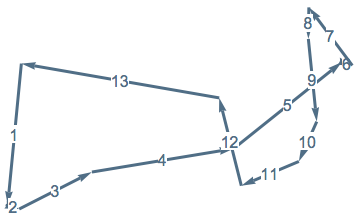

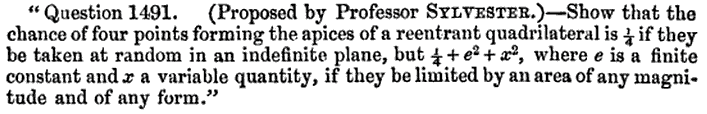

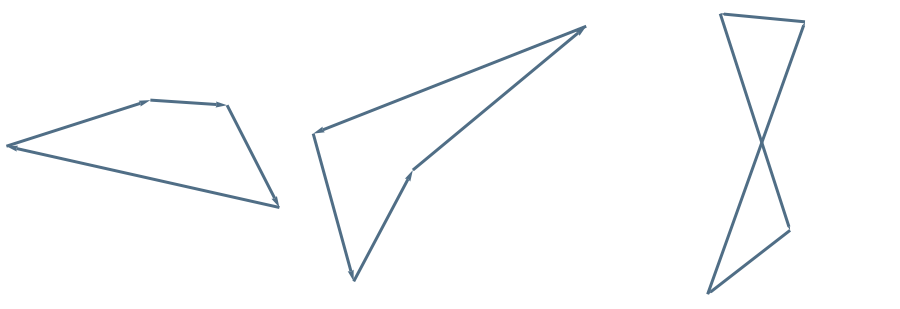

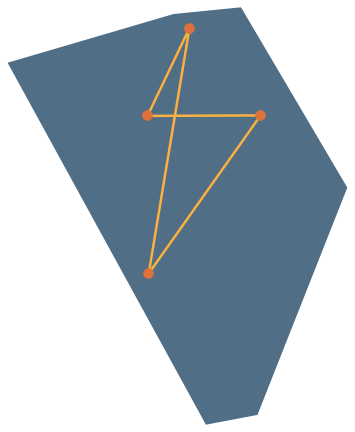

Sylvester’s Four Point Problem

convex

reflex/reentrant

self-intersecting

Modern Reformulation: What is the probability that all vertices of a random quadrilateral lie on its convex hull?

Some Answers

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{reflex})=\frac{1}{3}\)

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{reflex})=\frac{35}{12\pi^2}\approx 0.296\)

Theorem [Blaschke]

\(\frac{35}{12\pi^2}\leq\mathbb{P}(\text{reflex})\leq\frac{1}{3}\)

Our Answer

Theorem [w/ Cantarella, Needham, Stewart]

With respect to the symmetric measure, each of the three classes of quadrilaterals occurs with equal probability. In particular, \(\mathbb{P}(\text{reflex})=\frac{1}{3}\).

More generally...

Theorem [w/ Cantarella, Needham, Stewart]

With respect to any permutation-invariant measure on \(n\)-gon space, the probability that a random \(n\)-gon is convex is \(\frac{2}{(n-1)!}\).

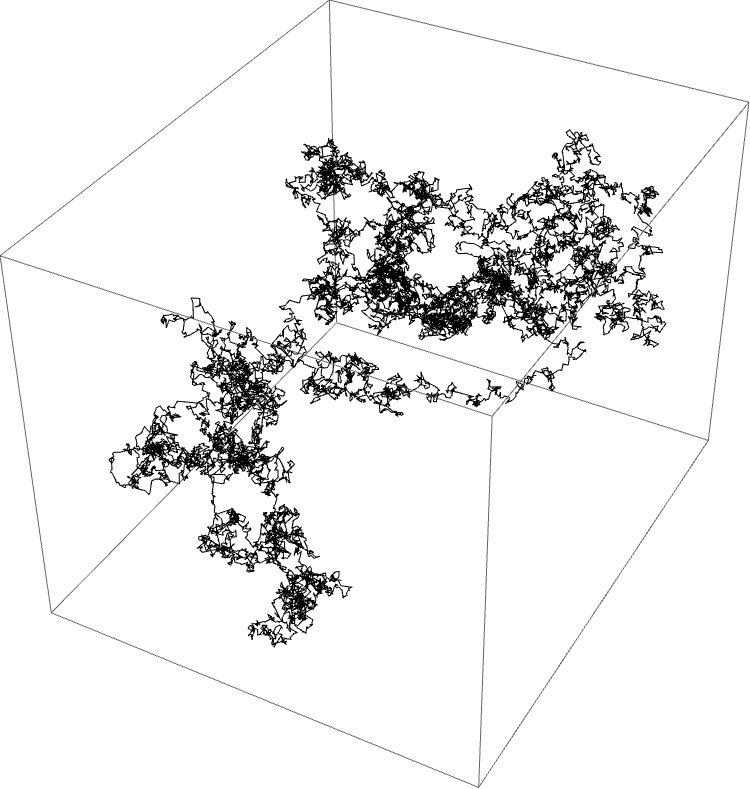

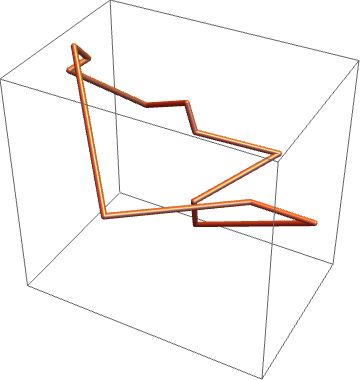

Polygons in Space

There is a version of this story for polygons in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) as well.

Example Theorem [w/ Cantarella, Grosberg, Kusner]

The expected total curvature of a random space \(n\)-gon is exactly

\(\frac{\pi}{2}n + \frac{\pi}{4} \frac{2n}{2n-3}\)

The polygon space is \(G_2(\mathbb{C}^n)\) and the analog of the squaring map is the Hopf map.

Open Problem

What is the manifold of equilateral planar \(n\)-gons up to translation and rotation?

Is there a good parametrization of this manifold?

Thank you!

References

- J. Cantarella, T. Deguchi, and C. Shonkwiler. Probability theory of random polygons from the quaternionic perspective. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 67 (2014), 1658–1699.

- J. Cantarella, A. Y. Grosberg, R. Kusner, and C. Shonkwiler. Expected total curvature of random polygons. American Journal of Mathematics 137 (2015), 411–438.

- J. Cantarella, T. Needham, C. Shonkwiler, and G. Stewart. Random triangles and polygons in the plane. Coming soon!

Square Roots of Angles

It turns out that if we take square roots of angles instead, we get:

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{obtuse}) = \frac{4-2\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{\pi}} \approx 0.661\)

But this approach doesn’t seem to generalize nearly as well as taking square roots of edgelengths.